Архив офтальмологии Украины Том 13, №2, 2025

Вернуться к номеру

Ретинальний вміст плазміногену і плазміну при експериментальній діабетичній ретинопатії та вплив фармакологічної блокади клітинних протеїнкіназ

Авторы: Усенко К.О., Михайловська В.В., Зябліцев С.В.

Національний медичний університет імені О.О. Богомольця, м. Київ, Україна

Рубрики: Офтальмология

Разделы: Клинические исследования

Версия для печати

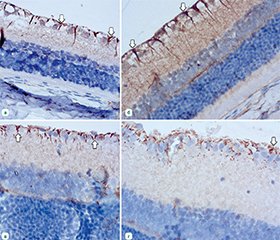

Актуальність. Діабетична ретинопатія (ДР) супроводжується порушенням регуляції протеолізу, зокрема активацією плазмінової системи, що сприяє нейрозапаленню та нейродегенерації сітківки. Вивчення ретинального вмісту плазміногену і плазміну та впливу фармакологічної блокади клітинних протеїнкіназ дозволяє уточнити роль цих компонентів у патогенезі ДР та обґрунтувати нові підходи до її патогенетичного лікування. Мета: визначити вміст у тканині сітківки плазміногену і плазміну та вплив на нього фармакологічного блокатора клітинних протеїнкіназ сорафенібу при експериментальній ДР. Матеріали та методи. У щурів-самців лінії Wistar моделювали ДР шляхом одноразового введення стрептозотоцину (50 мг/кг; Sigma-Aldrich, Co, China). Щурів було розподілено на 4 групи: контрольна, з введенням інсуліну (30 ОД; NovoNordiskA/S, Bagsvaerd, Denmark), інгібітору протеїнкіназ сорафенібу (Cipla, Індія) у дозі 50 мг/кг і з введенням інсуліну та сорафенібу. Імуноблотингове дослідження проводили з використанням моноклональних антитіл проти плазміногену і плазміну (Invitrogen, США). Результати. При розвитку експериментальної ДР за відсутності лікування відмічено суттєве накопичення в сітківці плазміногену і плазміну: збільшення через 28 діб та 2 місяці в 18,9 та 33,1 раза і в 10,5 та 12,7 раза відповідно (p < 0,001). Введення інсуліну та інгібітору протеїнкіназ сорафенібу як окремо, так і разом не впливало на приріст вмісту плазміногену. Приріст вмісту плазміну не змінювався при окремій дії інгібітору протеїнкіназ сорафенібу та гальмувався в 1,4–1,5 раза (p < 0,05) при дії інсуліну та комбінації інсуліну з сорафенібом. Експресія каспази-3 у контрольній групі суттєво збільшувалася в гангліонарних клітинах, відростках астроцитів та клітин Мюллера сітківки, відмічено розрідження гангліонарних клітин та ознаки їх дегенерації. Цьому запобігало введення інсуліну та комбінації інсуліну з сорафенібом. Висновки. При ДР відзначається суттєве накопичення плазміногену і плазміну в сітківці, що вказує на активацію плазмінової системи. Інсулін і його комбінація з сорафенібом частково знижують рівень плазміну та зменшують експресію каспази-3, запобігаючи нейродегенерації. Це підтверджує перспективність фармакологічної модуляції клітинних протеїнкіназ у ретинопротекції при ДР.

Background. Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is accompanied by dysregulation of proteolysis, in particular activation of the plasmin system, which contributes to neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration of the retina. The study of the retinal content of plasminogen and plasmin and the effect of pharmacological blockade of cellular protein kinases allows us to clarify the role of these components in the pathogenesis of DR and to substantiate new approaches to its pathogenetic treatment. Objective: to determine the content of plasminogen and plasmin in the retinal tissue and the effect of sorafenib, a cellular protein kinase inhibitor, on it in experimental DR. Materials and methods. DR was modeled in male Wistar rats by a single injection of streptozotocin (50 mg/kg; Sigma-Aldrich Co, China). Rats were divided into 4 groups: control; with the administration of insulin (30 U; Novo Nordisk A/S, Bagsvaerd, Denmark), a protein kinase inhibitor sorafenib (Cipla, India) at a dose of 50 mg/kg, and with the administration of insulin and sorafenib. Immunoblotting was performed using monoclonal antibodies against plasminogen and plasmin (Invitrogen, USA). Results. With the development of experimental DR in the absence of treatment, there was a significant accumulation of plasminogen and plasmin in the retina: after 28 days and 2 months, by 18.9 and 33.1 and by 10.5 and 12.7 times, respectively (p < 0.001). The administration of insulin and sorafenib both separately and together did not affect an increase in plasminogen content. An increase in plasmin level did not change with the separate action of the sorafenib and was inhibited by 1.4–1.5 times (p < 0.05) with insulin and the combination of insulin with sorafenib. The expression of caspase-3 in the control group significantly increased in ganglion cells, processes of astrocytes and Müller cells; ganglion cell loss and signs of their degeneration were noted. This was prevented by the administration of insulin and the combination of insulin with sorafenib. Conclusions. In DR, there was a significant accumulation of plasminogen and plasmin in the retina, which indicates the activation of the plasmin system. Insulin and its combination with sorafenib partially reduce plasmin level and caspase-3 expression, preventing neurodegeneration. This confirms the promising potential of pharmacological modulation of cellular protein kinases for retinal protection in DR.

діабетична ретинопатія; плазміноген; плазмін; сорафеніб

diabetic retinopathy; plasminogen; plasmin; sorafenib

Для ознакомления с полным содержанием статьи необходимо оформить подписку на журнал.

- Teo ZL, Tham YC, Yu M, et al. Global prevalence of diabetic retinopathy and projection of burden through 2045: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology. 2021;128(11):1580-1591. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2021.04.027.

- Medina-Ramirez SA, Soriano-Moreno DR, Tuco KG, et al. Prevalence and incidence of diabetic retinopathy in patients with diabetes of Latin America and the Caribbean: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2024;19(4):e0296998. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0296998.

- Flaxman SR, Bourne RRA, Resnikoff S, et al. Global causes of blindness and distance vision impairment 1990-2020: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2017;5(12):e1221-e1234. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30393-5.

- Wei L, Sun X, Fan C, Li R, Zhou S, Yu H. The pathophysiolo–gical mechanisms underlying diabetic retinopathy. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2022;10:963615. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2022.963615.

- Wang W, Lo A. Diabetic retinopathy: Pathophysiology and treatments. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(6):E1816. doi: 10.3390/ijms19061816.

- Whitehead M, Wickremasinghe S, Osborne A, Van Wijngaarden P, Martin KR. Diabetic retinopathy: A complex pathophysiology requiring novel therapeutic strategies. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2018;18(12):1257-1270. doi: 10.1080/14712598.2018.1545836.

- Wang W, Zhao H, Chen B. DJ-1 protects retinal pericytes against high glucose-induced oxidative stress through the Nrf2 signaling pathway. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):2477. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-59408-2.

- Sinclair SH, Schwartz SS. Diabetic retinopathy-an underdiagnosed and undertreated inflammatory, neuro-vascular complication of diabetes. Front Endocrinol. 2019;10:843. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2019.00843.

- van der Wijk AE, Hughes JM, Klaassen I, Van Noorden C, Schlingemann RO. Is leukostasis a crucial step or epiphenomenon in the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy. J Leukoc Biol. 2017;102(4):993-1001. doi: 10.1189/jlb.3RU0417-139.

- Xia F, Ha Y, Shi S, Li Y, Li S, Luisi J, et al. Early alte–rations of neurovascular unit in the retina in mouse models of tauopathy. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2021;9(1):51. doi: 10.1186/s40478-021-01149-y.

- Katz JM, Tadi P. Physiology, Plasminogen Activation. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan–. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK539745/.

- Polat SB, Ugurlu N, Yulek F, et al. Evaluation of serum fibrinogen, plasminogen, α2-anti-plasmin, and plasminogen activator inhibitor levels (PAI) and their correlation with presence of retinopathy in patients with type 1 DM. J Diabetes Res. 2014;2014:317292. doi: 10.1155/2014/317292.

- Persson M, Kjaer A. Urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR) as a promising new imaging target: potential clinical applications. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging. 2013;33(5):329-37. doi: 10.1111/cpf.12037.

- Sillen M, Declerck PJ. A Narrative Review on Plasminogen Activator Inhibitor-1 and Its (Patho)Physiological Role: To Target or Not to Target? Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(5):2721. doi: 10.3390/ijms22052721.

- Banfi C, Eriksson P, Giandomenico G, et al. Transcriptional Regulation of Plasminogen Activator Inhibitor Type 1 Gene by Insulin: Insights Into the Signaling Pathway. Diabetes. 2001;50(7):1522-30. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.7.1522.

- Yatsenko TA, Kharchenko SM. Polyclonal antibodies against human plasminogen: purification, characterization and application. Biotechnologia Acta. 2020;6(13):50-57. https://doi.org/10.15407/biotech13.06.050.

- Dabbs D. Diagnostic Immunohistochemistry: Theranostic and Genomic Applications. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2014. 960 p.

- Zhang X, Chaudhry A, Chintala SK. Inhibition of plasmi–nogen activation protects against ganglion cell loss in a mouse model of retinal damage. Mol Vis. 2003;9:238-48. Available from: http://www.molvis.org/molvis/v9/a35/.

- Chintala SK. Tissue and urokinase plasminogen activators instigate the degeneration of retinal ganglion cells in a mouse model of glaucoma. Exp Eye Res. 2016;143:17-27. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2015.10.003.

- Usenko KO. Effect of receptor protein kinase inhibition on the morphogenesis of experimental diabetic retinopathy. J Ophthalmol (Ukraine). 2025;1(522):47-53. doi: 10.31288/oftalmolzh202514753.

- Usenko KO, Rykov SO, Dyadyk OO, Ziablitsev SV. Effect of cellular protein kinases blockade on the S100 retina expression in experimental diabetic retinopathy. Pathologia. 2024;3(21):226-31. doi: 10.14739/2310-1237.2024.3.316604.

- Yatsenko T, Skrypnyk M, Troyanovska O, et al. The Role of the Plasminogen/Plasmin System in Inflammation of the Oral Cavity. Cells. 2023 Jan 30;12(3):445. doi: 10.3390/cells12030445.

- Giebel S, Menicucci G, McGuire P, et al. Matrix metalloproteinases in early diabetic retinopathy and their role in alteration of the blood-retinal barrier. Lab Invest. 2005;85:597-607. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700251.

- Mali RS, Cheng M, Chintala SK. Plasminogen activators promote excitotoxicity-induced retinal damage. FASEB J. 2005 Aug;19(10):1280-9. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-3403com.

- Wu SL, Zhan DM, Xi SH, He XL. Roles of tissue plasmino–gen activator and its inhibitor in proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Int J Ophthalmol. 2014 Oct 18;7(5):764-7. doi: 10.3980/j.issn.2222-3959.2014.04.

- Andreas P, Joachim S, Rolf MS, Helmut S. Growth Factor Alterations in Advanced Diabetic Retinopathy: A possible Role of Blood Retina Barrier Breakdown. Diabetes. 1997;46(Suppl 2):S26-S30. doi: 10.2337/diab.46.2.S26.

- Sirén V, Immonen I. uPA, tPA and PAI-1 mRNA expression in periretinal membranes. Curr Eye Res. 2003;27(5):261-267. doi: 10.1076/ceyr.27.5.261.17223.

- Das A, McGuire PG, Rangasamy S. Diabetic Macular Edema: Pathophysiology and Novel Therapeutic Targets. Ophthalmology. 2015;122(7):1375-1394. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.03.024.

- Sugimoto M, Cutler A, Shen B, et al. Inhibition of EGF signaling protects the diabetic retina from insulin-induced vascular leakage. Am J Pathol. 2013;183(3):987-995. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.05.017.

- Poulaki V, Qin W, Joussen AM, et al. Acute intensive insulin therapy exacerbates diabetic blood-retinal barrier breakdown via hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha and VEGF. J Clin Invest. 2002;109(6):805-815. doi: 10.1172/JCI13776.

- Klein R, Knudtson MD, Lee KE, Gangnon R, Klein BE. The Wisconsin Epidemiologic Study of Diabetic Retinopathy: XXII the twenty-five-year progression of retinopathy in persons with type 1 dia–betes. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(11):1859-1868. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.08.023.

- Tang J, Kern TS. Inflammation in diabetic retinopathy. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2011;30(5):343-358. doi: 10.1016/j.prete–yeres.2011.05.002.

- Vin H, Ching G, Ojeda SS, et al. Sorafenib suppresses JNK-dependent apoptosis through inhibition of ZAK. Mol Cancer Ther. 2014 Jan;13(1):221-9. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0561.

- Rahmani M, Davis EM, Crabtree TR, Habibi JR, et al. The kinase inhibitor sorafenib induces cell death through a process invol–ving induction of endoplasmic reticulum stress. Mol Cell Biol. 2007 Aug;27(15):5499-513. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01080-06.

- Lioutas VA, Novak V. Intranasal insulin neuroprotection in ischemic stroke. Neural Regen Res. 2016 Mar;11(3):400-1. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.179040.

- Liu J, Liu Y, Meng L, Ji B, Yang D. Synergistic Antitumor Effect of Sorafenib in Combination with ATM Inhibitor in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells. Int J Med Sci. 2017 Apr 9;14(6):523-529. doi: 10.7150/ijms.19033.

- Fenaroli F, Valerio A, Ingrassia R. Ischemic Neuroprotection by Insulin with Down-Regulation of Divalent Metal Transporter 1 (DMT1) Expression and Ferrous Iron-Dependent Cell Death. Biomolecules. 2024 Jul 15;14(7):856. doi: 10.3390/biom14070856.

- Stadelmann C, Lassmann H. Detection of apoptosis in tissue sections. Cell Tissue Res. 2000;301:19-31. doi: 10.1007/s004410000203.

- Ahmed M, Abu El-Asrar, Lieve Dralands, Luc Missotten, Ibrahim A Al-Jadaan, Karel Geboes. Expression of Apoptosis Markers in the Retinas of Human Subjects with Diabetes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45(8):2760-2766. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-1392.

- Mohr S, Xi X, Tang J, Kern TS. Caspase activation in retinas of diabetic and galactosemic mice and diabetic patients. Diabetes. 2002;51:1172-1179.

- Kowluru RA, Koppolu P. Diabetes-induced activation of caspase-3 in retina: effect of antioxidant therapy. Free Radic Res. 2002;36:993-999.

- Joussen AM, Doehmen S, Le ML, et al. TNF-alpha mediated apoptosis plays an important role in the development of early diabetic retinopathy and long-term histopathological alterations. Mol Vis. 2009 Jul 25;15:1418-28. PMID: 19641635.

- Sankaramoorthy A, Roy S. High Glucose-Induced Apoptosis Is Linked to Mitochondrial Connexin 43 Level in RRECs: Implications for Diabetic Retinopathy. Cells. 2021 Nov 10;10(11):3102. doi: 10.3390/cells10113102.

- Lam TT, Abler AS, Tso MOM. Apoptosis and caspases after ischemia-reperfusion injury in rat retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40:967-975.

- Hu Y, Xu Q, Li H, Meng Z, et al. Dapagliflozin Reduces Apoptosis of Diabetic Retina and Human Retinal Microvascular Endothelial Cells Through ERK1/2/cPLA2/AA/ROS Pathway Independent of Hypoglycemic. Front Pharmacol. 2022 Feb 24;13:827896. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.827896.

- Jasmiad N, Abd Ghani R, Agarwal R, et al. Relationship between serum and tear levels of tissue plasminogen activator and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 in diabetic retinopathy. BMC Ophthalmol. 2022;22:357. doi: 10.1186/s12886-022-02550-4.

- Barber AJ, Lieth E, Khin SA, Antonetti DA, Buchanan AG, Gardner TW. Neural apoptosis in the retina during experimental and human diabetes. Early onset and effect of insulin. J Clin Invest. 1998;102(4):783-791. doi: 10.1172/JCI2425.